Summary of what we can learn…

- The stigma from people promoting magnetic therapy products was already well established by 1880.

- Simple treatments can avoid the risk and side-effects of more toxic therapies.

- The concept of improving the magnetic apparatus used, what we refer to today as the optimisation process was already being contemplated.

In 1880, an article published in the Scientific American Supplement, by retired US Army Surgeon-General William Hammond M.D. stated…

That a magnet is capable of exercising a strong physiological influence over animals and even plants is a fact which, though overlooked or disregarded by physicians generally, experiment has definitely established. The reason for this neglect is doubtless to be found in the circumstances that the promulgators of the science of magnetism in its relations to life have generally mingled so much chaff with the grain of wheat that the latter has been lost sight of in the great superfluity of the former.

The same paper explains the “principle of suggestion”, that is of seeing and feeling as one is expected or told to see and feel. Other investigators, such as Baron von Reichenbach conducted experiments with magnets while taking every precaution to guard against such bias. Some of these experiments sounded somewhat similar to Mesmer’s work. Reichenbach noted that…“These sensitivities [to magnets] were almost invariably persons, mostly women, of strong neurotic temperaments.” Another physician wrote to a friend that…”if a magnet be brought into contact with a nervous subject, the magnetism produces many disquieting effects, and notably deranges the health. For my part, I do not think these disturbances are in any way due to the magnetic influence, whose real existence, however I do not contest: but I attribute them to the influence of the person’s imagination.”

Hammond quotes from an 1870 article published in the Journal of Psychological Medicine, titled On the Physiological Action of Magnetism. Written by a Dr John Vansant, Hammond describes it as the most philosophical and at the same time practical, essay on the action of magnetism on living beings. In 1866, Dr Vansant used a small magnetised steel rod with finely pointed ends and noted different pain responses when the north or south pole was brought in contact with a sensitive blister and on contact with the conjunctival membrane of the eye. He also noted different responses, when applying the north or south pole of a magnet over the painful areas of patients suffering from facial neuralgia.

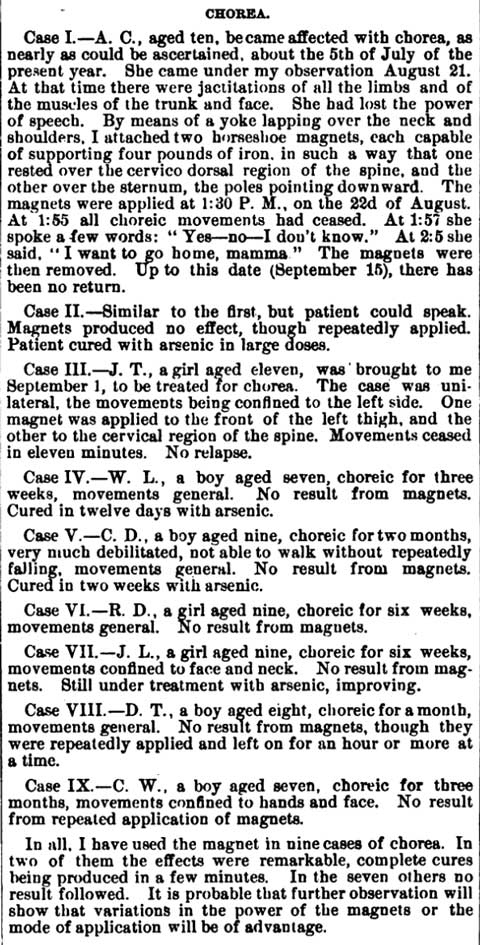

Hammond then records the results of nine cases, where applying horseshoe magnets on patients suffering from chorea, a type of neurological disorder causing abnormal involuntary movements. See Image.

What’s interesting to note is that of the nine cases, Hammond describes two as remarkable. Complete cures produced in a matter of minutes, while no benefits from the magnets were seen in the other seven. Of those seven however, at least four were subsequently treated with arsenic. This demonstrates that if the harmless magnets were not used, these patients would have most likely been given arsenic as a therapy and been exposed to its associated risks and side-effects.

Also of interest, Hammond writes…“It is probable that further observations will show that variations in the power of magnets or the mode of application will be of advantage.” This is the first known reference from a magnetic field therapy practitioner that mentions the concept of optimisation of the static magnetic field to improve the clinical outcomes for patients.

This is quite remarkable, since the manufacture of magnets was still relatively primitive. It wasn’t until the 1940’s, with the introduction of Ferrite and Alnico magnets, were increases in field strength even possible. Then in the 1980’s with the introduction of even more powerful neodymium rare earth magnets and even more importantly, multipolar magnet arrays opened up a whole new era in the application and physiological effects of static magnetic fields.

REF:

Hammond W.A., (1880). The Therapeutic use of the Magnet. Scientific American Supplement: 258. (4112-4114).

Accessed: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000018628104;view=1up;seq=810;size=200