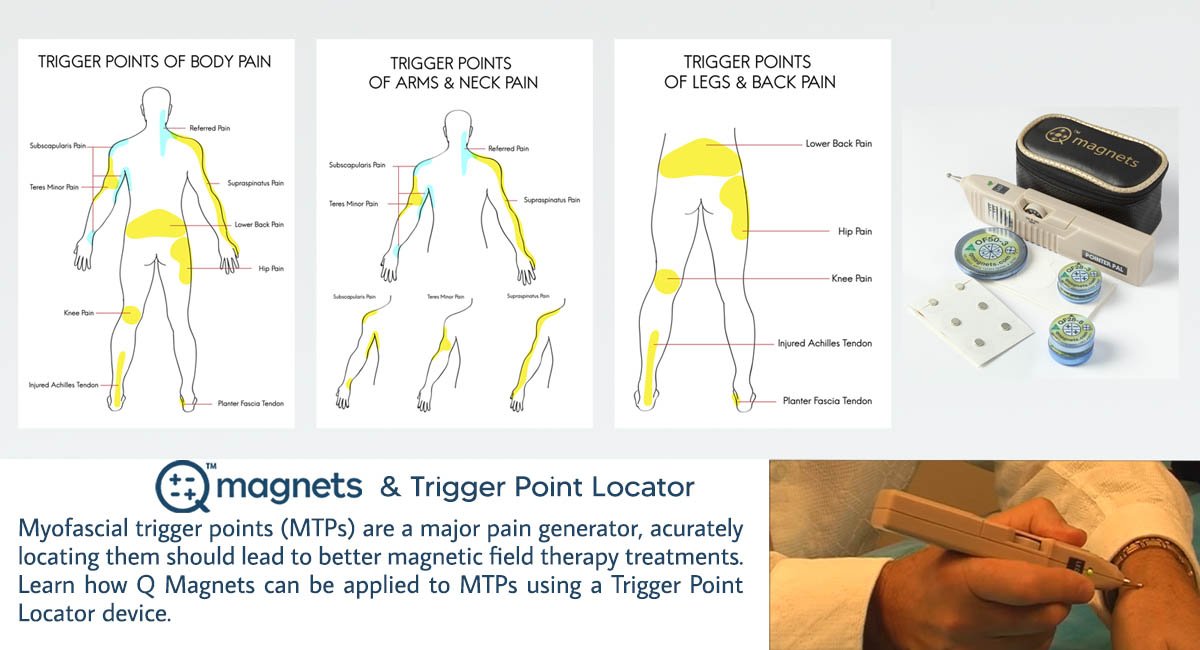

Myofascial Trigger Point Locator and Q Magnet Application

Active trigger points are a major cause of myofascial pain syndromes. Many doctors and therapists use a trigger point locator and Q Magnets as an adjunct in therapy to treat active trigger points.

While the larger more powerful and deeper penetrating devices such as the QF28-6 are best if their target is one of the larger nerves, such as the sciatic nerve. The smaller inexpensive Q Magnet such as the QF10-2 or Q6-1.5 might be large enough to place over superficial trigger points.

By accurately locating myofascial trigger points (MTPs), a consumer or practitioner of neuromagnetic therapy is able to target the area with a smaller, more comfortable and affordable Q Magnet device without diminishing the effect. MTPs are a major pain generator, acurately locating them should lead to better treatments.

The following video shows Doug Edwards, an experienced user of the device briefly describing the how to and why of a trigger point locator:

The next video demonstrates how simple it is to apply the Q6-1.5 to a trigger point.

Pointer Pal – Trigger Point Locator

- Hand held Trigger Point Locator

- Helps identify precise application points

- Includes hand-held grounding electrode,

- 2 probe tips (2mm 0.08″ and 4mm 0.16″),

- 9V battery, case and instructions

- Glides over active Trigger Points and emits buzzing sound while the pilot light flashes

AUD$ 77

One of the benefits of Q Magnets application is that unlike therapies such as dry needling or laser therapy, they can easily be worn continuously between treatments. Read on to see what the research says in this area and how to get the best results.

THE RESEARCH:

Three studies have shown positive effects of multipolar magnets on trigger points:

- Vallbona et al conducted a controlled trial to investigate the treatment of chronic pain experienced by post-polio patients with identified painful trigger points with a multipolar magnet and found a significant and prompt relief of pain.

- Brown et al investigated the treatment of chronic pelvic pain with a multipolar magnet applied to abdominal trigger points and at the end of the intervention patients with the active magnet had significantly lower Pain Disability Index.

- Smania et al conducted an RCT comparing the effects of short, medium and long term treatment with repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS), TENS and placebo treatment on myofascial pain syndrome (MPS). The authors concluded that the therapeutic benefits of rMS lasted much longer than TENS and that rMS may be a novel, non-invasive, and reliable therapeutic approach for MPS.

Hazlewood and Markov discussed the potential of using permanent magnets placed over trigger points but failed to recognise the importance of segmental central sensitization. The persistent pain of MTPs can lead to neuroplastic changes in the spine, leading to secondary hyperalgesia and the amplification of the pain sensation (REF 1).

A number of experienced clinicians have observed that where central sensitization is diagnosed, targeting the affected spinal segments with the larger Q Magnet devices (that have the necessary depth of penetration) will in many cases dampen or “turn off” the sensitization. Where there are two adjacent levels affected such as L4/5 and L5/S1 the octapolar OF50-3 model can be used. At 50mm in diameter, the OF50-3 is large enough to cover both levels and also powerful enough to envelope the spinal segments with a therapeutic field.

Studies in the past including Collacott failed to prove efficacy of the magnetic device because the device was too weak to penetrate to the target tissue, this is now possible with Q Magnet therapy.

THE APPLICATION:

Myofascial pain starts with a sudden and sustained muscular contraction in a localised area. This type of pain is focused in areas of MTPs located in one or more of the affected muscles. Active MTPs are painful, quite small (3-5mm in diameter) and highly localised hyperirritable regions with palpable taut bands of skeletal muscle.

Locating MTPs, even with examination by experienced health practitioners is not always reliable. An objective measure such as a skin resistance measuring device or point locator can be a useful tool to confirm manual diagnosis.

Skin resistance and its reciprocal, skin conductance, are terms used to identify the skin’s ability to resist or transmit electric current. Pain is a primary factor influencing the skin’s capacity for electricity and specifically decreasing skin resistance. The biochemical changes seen in active MTPs are a result of painful stimuli increasing the rate of blood flow and sweat secretion from sweat glands and ducts. The increased sweat content can account for variations in skin resistance. Several studies have documented the accuracy of skin conductance measurements as a method for identifying acupuncture points (REF 2).

Acupuncture points (APs) have also been associated with areas of low electrical skin resistance but are mainly located along the body’s meridians. There are other points not associated with meridians but there is a strong correlation between acupuncture points and myofascial trigger points. However, acupuncture points located at trigger points “are not frequently used by acupuncturists and do not share the same clinical indications as the trigger point therapy (REF 3)”

There still remains plenty of debate regarding the accuracy of skin resistance readings to locate acupuncture points. One placement option for Q Magnet therapy is applying the devices using adhesive plasters over MTPs. From the feedback of experienced manual therapists, the use of trigger point locators has proven to be an effective tool to precisely locate hyperactive nerves where the unique field generated by Q Magnets have the best physiologic effects.

There are number of skin resistance point locators on the market, we recommend the Pointer-Pal as it’s reliable and reasonably priced.

Once the location of the MTPs have been found, then the appropriate Q Magnet device can be placed over that point. There are a number of Q Magnet sizes for different applications. See Q Magnet models.

For instance you can apply the QF15-2 model which has a 15mm diameter and is 2mm thick. To achieve a greater penetration, select a thicker device such as the QF15-3 which is 15mm in diameter and 3mm thick. A wider diameter magnet will simply cover a larger skin surface and potentially more nerves, while the thickness and strength of the magnet is what determines depth of penetration of the field.

Published research on myofascial trigger points, acupuncture points and electrical skin resistance:

Response of Pain to Static Magnetic Fields in Postpolio Patients: A Double-Blind Pilot Study Vallbona C, Hazlewood CF, Jurida G Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Nov;78(?):1200-1203 Efficacy of static magnetic field therapy in chronic pelvic pain: a double-blind pilot study. Brown CS, Ling FW, Wan JY, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1581-7. Repetitive magnetic stimulation: A novel therapeutic approach for myofascial pain syndrome. Smania N, Corato E, Fiaschi A, Pietropoli P, Aglioti SM, Tinazzi M J Neurology. 2005; 252(3):307-314 Could the relief of myofascial and/or low back pain by magnetic fields be explained by their action on trigger points?CONCLUSIONS: There is evidence that the application of magnetic fields (via permanent magnets) on trigger points is more effective for pain relief as compared to application to other body surface area.

Hazlewood CF, Markov MS Environmentalist. 2007; 27:447-451 Recognition of central sensitization in patients with musculoskeletal pain: Application of pain neurophysiology in manual therapy practice. CONCLUSIONS: By using our current understanding of central sensitization during the clinical assessment of patients with musculoskeletal pain, manual therapists can apply the pure science of nociceptive and pain neurophysiology to the practice of manual therapy. The diagnosis of central sensitization in individual patients with musculoskeletal pain is not straightforward, however manual therapists can use information obtained from the medical diagnosis, history taking of the patient, clinical examination, and the analysis of the treatment response to recognize central sensitization. The outcome of the diagnostic process can be used to determine the appropriate treatment parameters (e.g. intensity and frequency of various manual therapy techniques). Nijs J, Van Houdenhove B, Oostendorp R Manual Therapy . 2010; 15:135–141 The evaluation of electrodermal properties in the identification of myofascial trigger points. CONCLUSIONS: The changes in skin resistance between the MTP and the surrounding tissue support the inclusion of this technique to help identify MTPs. The similarity between MTP states warrants investigation into the physiologic differences at specific anatomic locations. Shultz SP, Driban JB, Swanik CB. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 Jun;88(6):780-4. Electrical skin resistance and thermal findings in patients with lumbar disc herniation. CONCLUSIONS: Electrical skin resistance is more sensitive and early in detecting sympathetic dysfunction in patients with lumbar disc herniation than skin temperature. Also, this test is cheap, easy for both the patient and the physician to be performed, and helpful in the follow-up of patients with lumbar disc herniation, after physical therapy and/or surgery. Tuzgen S, Dursun S, Abuzayed B. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2010 Aug;27(4):303-7. An electrophysiological approach to the evaluation of regional sympathetic dysfunction: a proposed classification. The term electrodermography (EDG) is currently used to encompass the wide range of electrophysiological measurements related to skin that were previously known as the galvanic skin response (GSR). While the original term GSR was intended to be used solely to represent one specific electrical skin phenomenon, it eventually became widely applied to all forms of electrodermal measurement. Longmire, DR Pain Physician. 2006;9:69-82 Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: Correlations and implications ABSTRACT: Trigger points associated with myofascial and visceral pains often lie within the areas of referred pain but many are located at a distance from them. Furthermore, brief, intense stimulation of trigger points frequently produces prolonged relief of pain. These properties of trigger points — their widespread distribution and the pain relief produced by stimulating them — resemble those of acupuncture points for the relief of pain. The purpose of this study was to determine the correlation between trigger points and acupuncture points for pain on the basis of two criteria: spatial distribution and the associated pain pattern. A remarkably high degree (71%) of correspondence was found. This close correlation suggests that trigger points and acupuncture points for pain, though discovered independently and labeled differently, represent the same phenomenon and can be explained in terms of the same underlying neural mechanisms. The mechanisms that play a role in the genesis of trigger points and possible underlying neural processes are discussed. Melzack R, Stillwella DM, Fox EJ Pain 1977;3:3-23 The Status and Future of Acupuncture Mechanism Research The analogy between trigger points and acupuncture points became widely discussed since Melzack et al.’s landmark study in 1977. There are a number of similarities between the two: the two structures have similar locations; needles are used at both points to treat pain; the pain associated with the local twitch response at trigger points is similar to the de qi sensation; and the referred pain generated by needling trigger points is similar to the purported propagated sensation along the meridians. However, the acupoints located at these trigger points are not frequently used by acupuncturists and do not share the same clinical indications as the trigger point therapy. Trigger points may represent a subset of acupuncture points—specifically, the ah shi points. Napadow V, Ahn A, Longhurst J, Lao L, Stener-Victorin E, Harris R, Langevin HM. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Sep;14(7):861-9. Skin Impedance Measurements for Acupuncture Research: Development of a Continuous Recording System. CONCLUSION: We conclude that our system is a suitable device upon which we can develop a fully automated multi-channel device capable of recording skin impedance at multiple APs simultaneously over 24 h. Colbert AP, Yun J, Larsen A, Edinger T, Gregory WL, Thong T. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008 Dec;5(4):443-50 Characteristics of Electrical Skin Resistance at Acupuncture Points in Healthy Humans. CONCLUSIONS: This study shows that electrical skin resistance at APs can either be lower or higher compared to the surrounding area. The phenomenon is characterized by high short-term and low long-term reproducibility. Therefore, we conclude that APs might possess specific transient electrical properties. However, as the majority of the measured APs did not show a changed ESR, it cannot be concluded from our data that electrical skin resistance measurements can be used for acupuncture point localization or diagnostic/therapeutic purposes. (This paper should be read in conjunction with the comments by A Colbert below) Kramer S, Winterhalter K, Schober G, Becker U, Wiegele B, Kutz DF, Kolb FP, Zaps D, Lang PM, Irnich D. J Altern Complement Med. 2009 May;15(5):495-500. The ongoing debate: do acupuncture points have lower skin resistance than nonacupuncture sites? My conclusion regarding the findings of Kramer et al. is more guarded than theirs. Before calling a halt to the use of skin resistance measurements for localization of acupuncture points, I propose that we precisely replicate the study design of Becker et al. Until Becker et al.’s outcomes are either confirmed or disproved, the spirited debate as to whether APs have lower skin resistance needs to continue. Colbert AP J Altern Complement Med. 2009 May;15(10):1059. Electrophysiological correlates of acupuncture points and meridians. CONCLUSIONS: Electrical correlates have been established for a portion of the acupuncture system and indicate that it does have an objective basis in reality. Thus far, the data are supportive to our general theory of the action of the acupuncture technique as influencing a primitive data transmission and control system. Becker R, Reichmanis M, Marino A, Spadaro J. Psychoenergetic Systems 1976;1:105–112. Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: A systematic review. Ahn AC, Colbert AP, Anderson BJ, et al. Bioelectromagnetics 2008;29:245–256.Q Magnets Presentation at ICMART 2023

On Saturday, 30th September, James Hermans (co-founder and co-inventor of Q magnets) gave a presentation at the International Medical Acupuncture Conference in Amsterdam (ICMART 2023). The main theme of the talk was…“Static medical magnets are a promising...

New Article in the Medical Acupuncture Journal on Static Multipolar Magnets

A new article published in the Medical Acupuncture Journal shows the potential of multipolar magnets for pain relief. The authors studied a recent series of cases submitted from the practices of 4 different medical acupuncturists and concluded that if static magnetic field therapy is properly employed, it can be an effective and safe modality for treating pain.

Q Magnets Case Study Published in the Medical Acupuncture Journal

Medical acupuncturists are experts at identifying and accurately locating the morphological structures to be targeted. Quadrapolar, or Q Magnets produce an optimised field and provide the acupuncturist with an additional modality to target these structures that is...

Alfred says, “These are serious elite products for pain management” and he sings “I’m a believer!” by The Munkees!

Thanks for the good service and fast delivery. Your products are clearly first rate; and the magnetic strength of these products is remarkable. These are serious elite products for pain management. From the moment I put on the strong magnets, my back pain quickly...